This is part one of a two-part series on the history of the Gunnar Mine, based on the book Gunnar Uranium Mine: Canada’s Cold War Ghost Town written by SRC's President Emeritus, Dr. Laurier Schramm. SRC is managing the Gunnar Mine and Mill Site remediation, as well as 36 other abandoned uranium mine sites in northern Saskatchewan. Learn more about Project CLEANS.

This is a contributed post written by former SRC President and CEO, Dr. Laurier Schramm.

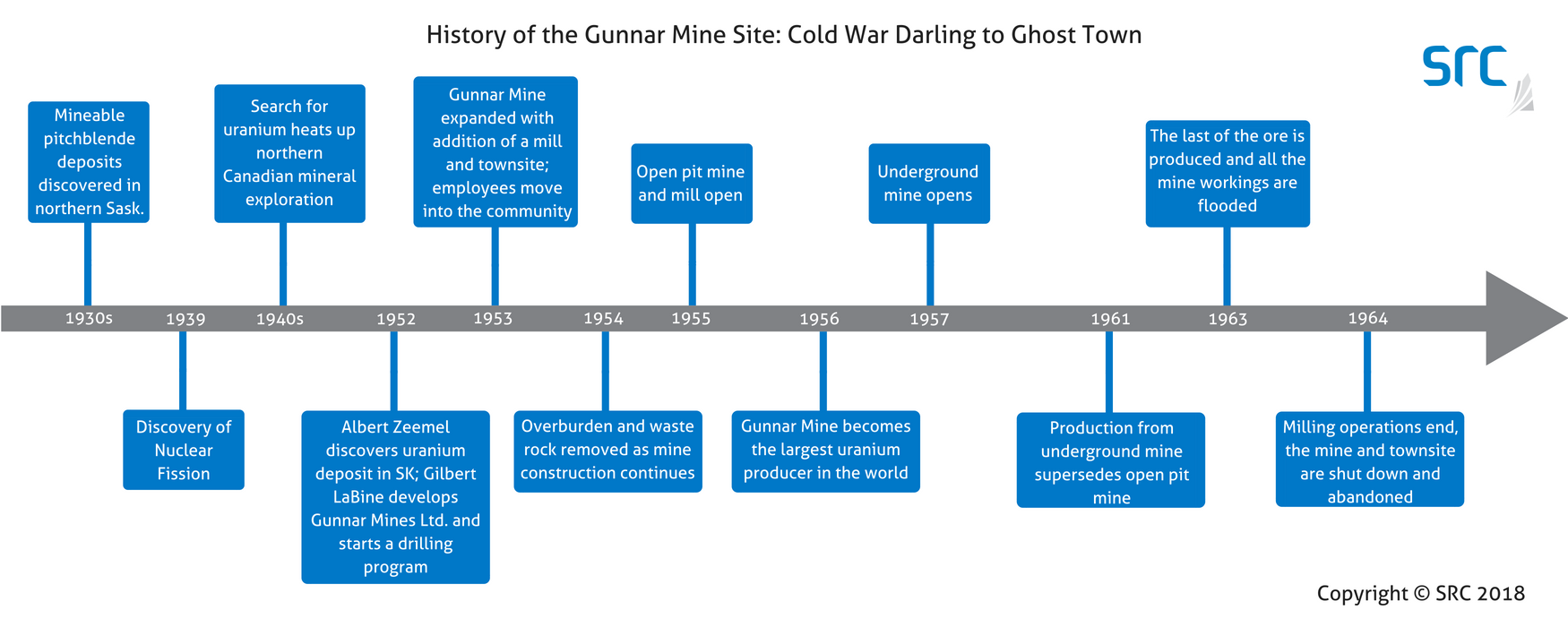

In the early 1930s, prospectors discovered mineable deposits of Canadian pitchblende near Lake Athabasca in northern Saskatchewan. Uranium wasn’t much more than a curiosity at that time, but it became instantly valuable when the 1939 discovery of nuclear fission and its massive energy-producing potential led to an international atomic energy race.

The worldwide search for uranium caused a resurgence in northern Canadian mineral exploration through the 1940s. In the early 1950s, many uranium mines were developed in the Beaverlodge region of northern Saskatchewan.

This era is rich in stories, involving a high-stakes treasure hunt in a remote, northern wilderness, the secrecy, intrigue, and urgency of the Cold War, plus adventures and hardships of all kinds. Although there were many failures, a few remarkable successes were born of a combination of hard work, good fortune, creativity, and dogged persistence. The results made Canada one of the world’s largest sources of uranium.

One such story is that of the Gunnar Mine.

Uranium discovery in northern Saskatchewan

In 1952, Albert Zeemel found and staked a uranium deposit at the southern tip of the Crackingstone Peninsula on the north shore of Lake Athabasca, the 22nd largest lake in the world. It was probably just as well that Zeemel was a complete newcomer to uranium prospecting because he’d been searching in an area that professionals believed only a fool would bother to prospect. Zeemel, on the other hand not only found a uranium deposit there, it was considered to be the richest uranium strike in Canada at the time.

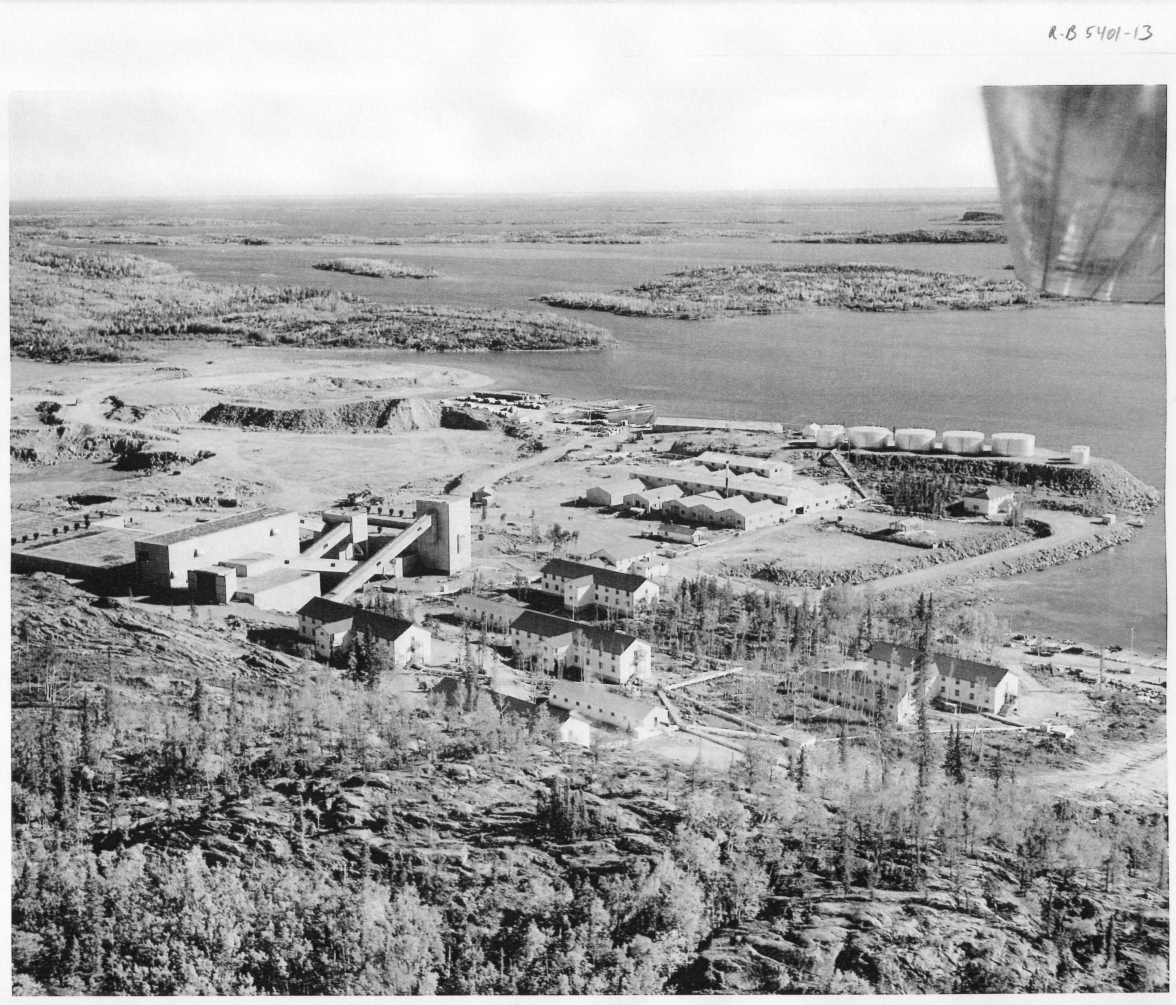

From this deposit, Gilbert LaBine, Canada’s “Mr. Uranium,” developed Gunnar Mines Ltd. as the first large private uranium mine of the era. They started a drilling program in 1952, expanded it in 1953, and within two more years the mine was in production. Although the Gunnar deposit is usually described as being “near” Uranium City, it is actually about 40 km away and with no road access, it was decided a mill and a dedicated community would be built in addition to the mine. Construction for these commenced in 1953.

Construction challenges in a remote location

Building a mine, mill, and town was not as easy as it might sound. Being in a remote location, most construction and other materials had to be brought in by boat or barge, or else by air. In 1954, the aircraft had to land on the lake when it was frozen, but eventually Gunnar bought its own DC-3C aircraft and built its own dedicated airstrip near the mine site.

Since the cost of freight by air was more than double that by water, a year’s worth of supplies would be ordered before the beginning of each boat/barge season for delivery in advance of winter freeze-up.

This became such a large undertaking that Gunnar eventually developed its own dedicated shallow-draft tugboat and barge system for shipping goods along the 440-km route from the railhead at Waterways, Alberta. Although only about 15 weeks per year were practical for waterborne transportation, many tens of thousands of tonnes of freight were transported in this manner, and at great expense.

Pushing the limits of the seasons was risky, as Gunnar learned in 1956 when a tugboat and eight barges froze into the ice. Gunnar Mines would find that their capital and operating costs would both be more than double those of comparable southern mines.

The Gunnar townsite

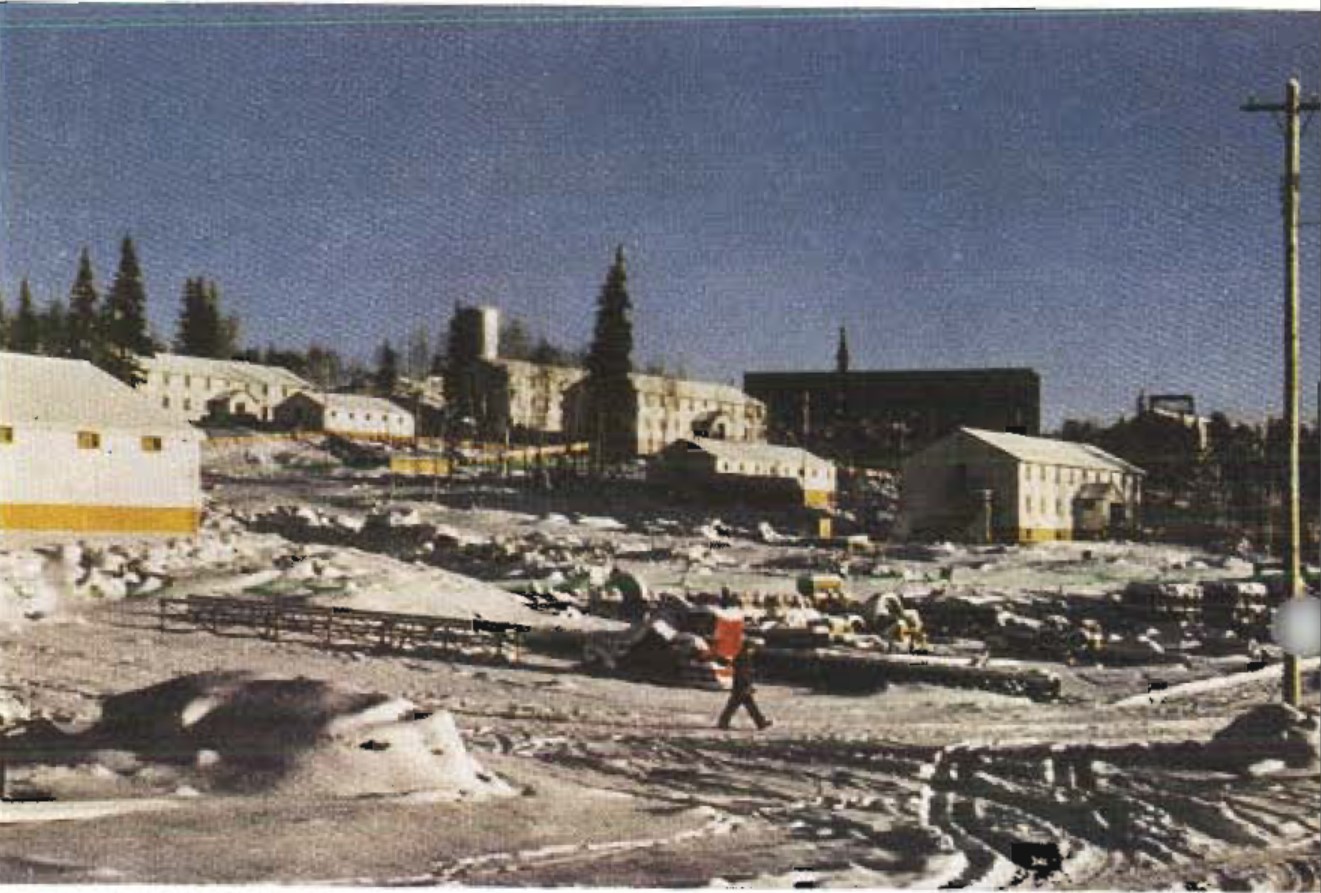

To support its operations, the company built and managed a complete townsite. Employees started moving to the townsite in 1953, and between then and 1958, the Gunnar townsite grew to include seven two-story bunkhouse dormitories, two apartment buildings, 86 houses, a school, a hospital, a community centre, and recreational facilities ranging from bowling alleys, to a curling rink, to lake-side cabins and a marina.

The two-level community centre included both shopping and community facilities, was centrally heated, and was North America’s first covered shopping mall. The townsite had to be self-sufficient, which included generating all power, heat, and other utilities onsite. Between 1958 and 1961 the town’s population was relatively steady at about 800.

The largest uranium producer in the world

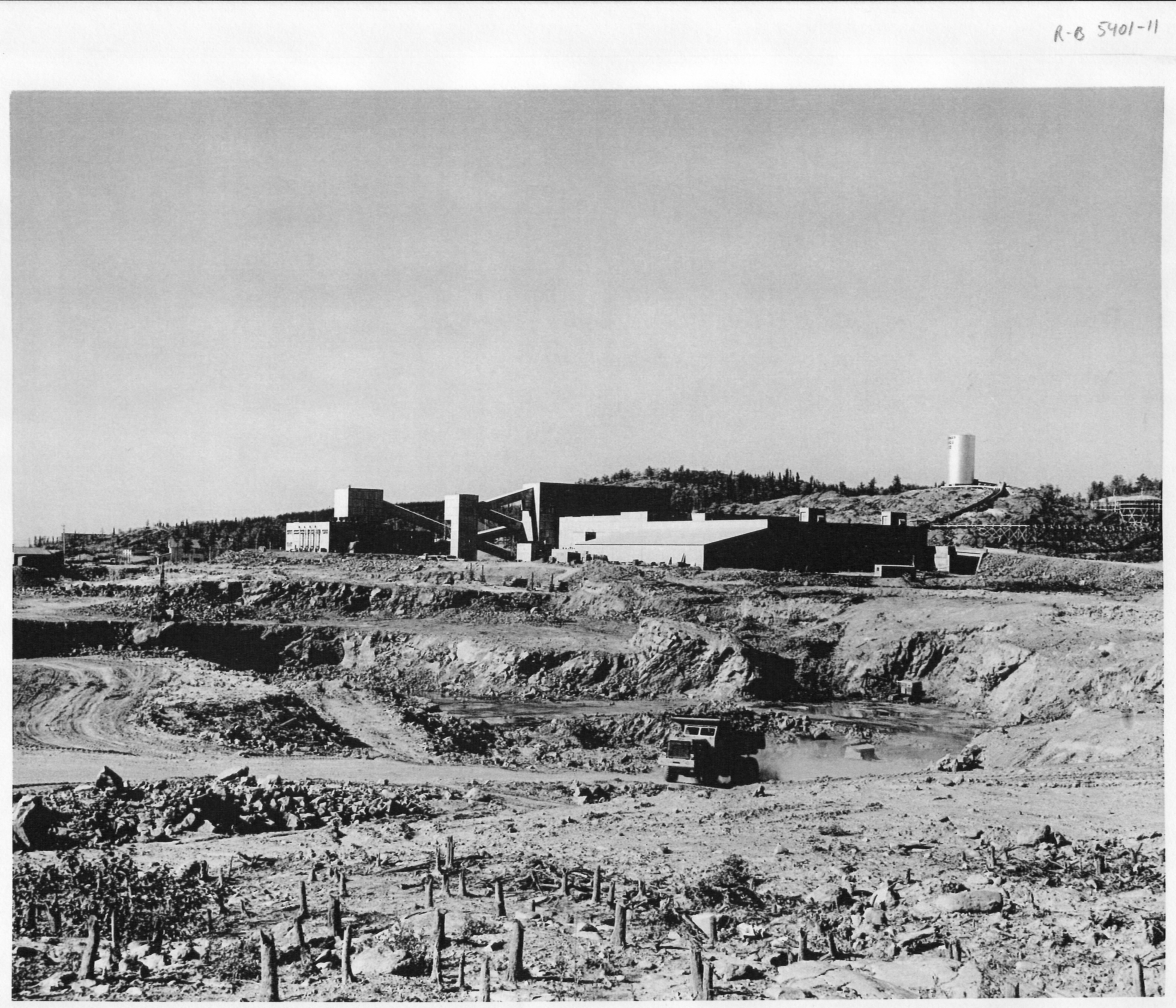

By the fall of 1953 enough bush had been cleared to make room for the mill and initial camp buildings, and construction began on workshops and warehouses. In 1954, about 270,000 m³ of overburden, comprising permafrost muskeg and glacial silt, were removed. In addition, over a million tonnes of surface waste rock had to be blasted and removed. Just like for the mine and mill that were to come later, these operations continued 24 hours a day, seven days a week, and in all types of weather.

The open pit mine and mill opened in 1955 and, by 1956, Gunnar was the largest uranium producer in the world. The open pit was roughly oval in shape and was mined by blasting followed by power shovels, to a final depth of 110 m below the level of the lake. The mining followed a major “pipe-like” pitchblende vein that extended downward over 440 m from the surface at a 45° angle, through a body of altered granite.

Everything excavated from the open pit - uranium ore and waste rock alike - had to be carried to the surface by trucks. By the time the open pit had been mined to its final size, the driving distance from the bottom of the pit to the mill was nearly 2 km.

The underground mine and hoist system went into operation in May 1957, and completely superseded open pit production by late 1961. The underground mine was developed by drilling and blasting, with the ore being moved along the haulage levels by rail, and then hoisted to the surface. By the end of 1962, the shaft had been extended to 604 m, providing access to 13 discrete levels.

No shortage of mining challenges

There were numerous mining challenges, of course. As underground mining progressed water was encountered at most levels, and had to be semi-continuously pumped out. During winter operations, ore had to be moved to the mill as soon as possible after blasting otherwise, if allowed to cool and crushed when cold, it tended to adhere to conveyor belts and ore bins.

Compared with Saskatchewan’s modern uranium mines, the ore grade at Gunnar was extremely low. Most of the ore mined and sent for milling was about 0.18 to 0.19% (as U3O8), meaning that proportionately huge amounts of rock had to be mined, transported, and milled in order to produce the uranium.

The end of an era

The end of an era

The last of the ore was produced in late 1963: over its operating lifetime, the Gunnar mine produced over 5 million tonnes of uranium ore, which was milled to produce over eight thousand tonnes of uranium concentrate (U3O8, “yellowcake”). This was packed into 25-gallon steel drums weighing 450-500 pounds each and flown from the Gunnar airstrip to Edmonton, usually by Gunnar’s own plane, a Douglas DC-3C. From Edmonton, they were shipped to Eldorado’s refinery at Port Hope, Ontario.

By October of 1963, Gunnar’s reserves were gone, all mining operations ended, and the entire above- and below-ground mine workings were completely flooded. By February of 1964, all milling operations ended, and the entire site was rather abruptly shut-down – without any decommissioning or reclamation.

That same year, the Gunnar townsite population dropped from 800 to 1: a single caretaker. The entire Gunnar site had become a ghost town.

But the story isn’t over – stay tuned for part 2 of this series where I’ll dive into the Gunnar Mine’s legacy and the environmental hazards created by its closure.

Reference

Schramm, L.L., Gunnar Uranium Mine: Canada’s Cold War Ghost Town, Saskatchewan Research Council, Saskatoon, and Amazon.com Inc., 2016.